How Fatigue, Illness, and Overtraining Impact Your Resting Heart Rate

Whether You Can Use this Information to Train Smarter.

When I was in high school, my cross country coach issued us custom-made running logs. Each page had four columns: date, workout & comments, hours of sleep, and resting heart rate.

These first three columns are all good things to track, but what about resting heart rate?

My coach believed that checking your resting heart rate every day when you wake up in the morning could alert you if you were overtraining or beginning to get sick.

Was he right?

Sheepishly, I have to admit I was never diligent enough to actually track my resting heart rate every day. I’d check it every now and then, so I’d have a ballpark of what was “normal” for me, and my resting heart rate definitely rose—sometimes increasing by 70-100%—while I was sick. Intuitively, this makes some sense, as illness puts more stress on your body.

Unfortunately, when it comes to illness and resting heart rate, there’s very little in the way of scientific research.

Online sources like WebMD and the American Heart Association assert that being sick does indeed raise your resting heart rate, but there’s no hard data that I can find on how reliable this is, whether the magnitude of the increase in heart rate is related to the severity of the illness, or whether resting heart rate spikes before the onset of other symptoms.

Fortunately, with the advent of cheap, wearable heart rate monitors, a study investigating these questions shouldn’t be too hard to conduct. If you’re a doctor or researcher, here’s your chance to get published!

However, the research on resting heart rate and overtraining is a different story.

In this article, we’ll examine what the research says and whether you can use this information to train smarter.

Overtraining and resting heart rate

In a healthy runner, the body responds positively to a new stress in training, like increasing your mileage or going further on your long run. But if you’re in a state of overtraining, or “overreaching,” its less-severe cousin, your body rebels against the training stimulus and you feel listless, abnormally sore, irritable, and fatigued.

Additionally, you may have trouble sleeping, and your workouts and races will go poorly.

Since overtraining is difficult to observe in a controlled fashion when it “naturally” occurs (i.e. when athletes unintentionally overdo it by training too hard), most studies instead intentionally induce overtraining by having a small group of athletes vastly increase their training load over a short period of time.

In many cases, this reliably induces the same symptoms as unintentional overtraining.

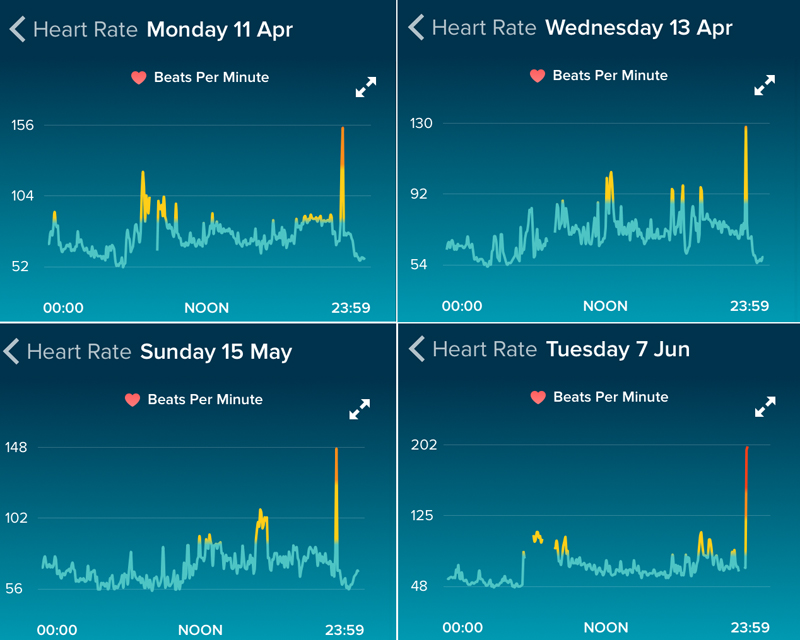

One such study by Asker Jeukendrup and other researchers at the University of Limburg in The Netherlands observed seven male cyclists who upped their normal training intensity for a two-week block. Among other things, Jeukendrup et al. measured the athletes’ heart rate while they slept at night.

After the two-week jump in training, all of the athletes were fatigued and performed worse in a time trial when compared to the testing done at the study’s outset. Additionally, sleeping heart rate increased from an average of 49 beats per minute to 54.

In contrast, a similar study of distance runners came to a different conclusion.

Verde, Thomas, and Shephard of the University of Toronto in Canada studied 10 runners with an average 10k PR of 31:04 who undertook a 40% jump in training over a three-week period. Six of the 10 runners reported sustained fatigue during the increased training block, and two suffered upper respiratory infections.

There was a very small and statistically insignificant trend towards higher resting heart rates during the period of heavy training, and a similar (though also non-significant) drop during the recovery period after the three-week block, but the authors noted that the magnitude of the change—less than two beats per minute, from about 51 to 53 beats per minute—was far too small to be a useful measurement for athletes in the real world.

Sleeping heart rate fluctuations

A 2003 review article by Juul Achten and Asker Jeukendrup (lead author of the first study we examined) cited four other scientific studies which found no correlation between overtraining and increased resting heart rate.

They did, however, cite one additional study which found an increase in sleeping heart rate to be associated with overtraining.

Achten and Jeukendrup hypothesize that heart rate during sleep is a more reliable marker of your body’s recovery state.

Resting heart rate can jump up or down by several beats per minute for any number of reasons, and nighttime heart rate measurements can be measured and averaged over much longer durations than the typical 30 seconds or one minute that it takes to measure resting heart rate.

Conclusion

The research suggests that by itself, your resting heart rate is likely not all that useful of a measurement.

If you are worried about overtraining, it’s probably better to pay close attention to things like your fatigue level, workout times, and sleep quality.

If these start going poorly, you should watch out, regardless of what your resting heart rate is doing.

When it comes to illness, the jury’s still out—there’s no good research on resting or sleeping heart rate when you’re sick with a cold or the flu.

It will probably go up when you get sick, but it’s not clear by how much, and whether heart rate spikes before or after other symptoms of illness appear.

More research is also needed on the value of sleeping heart rate—is it a more reliable and sensitive predictor of overtraining or illness?